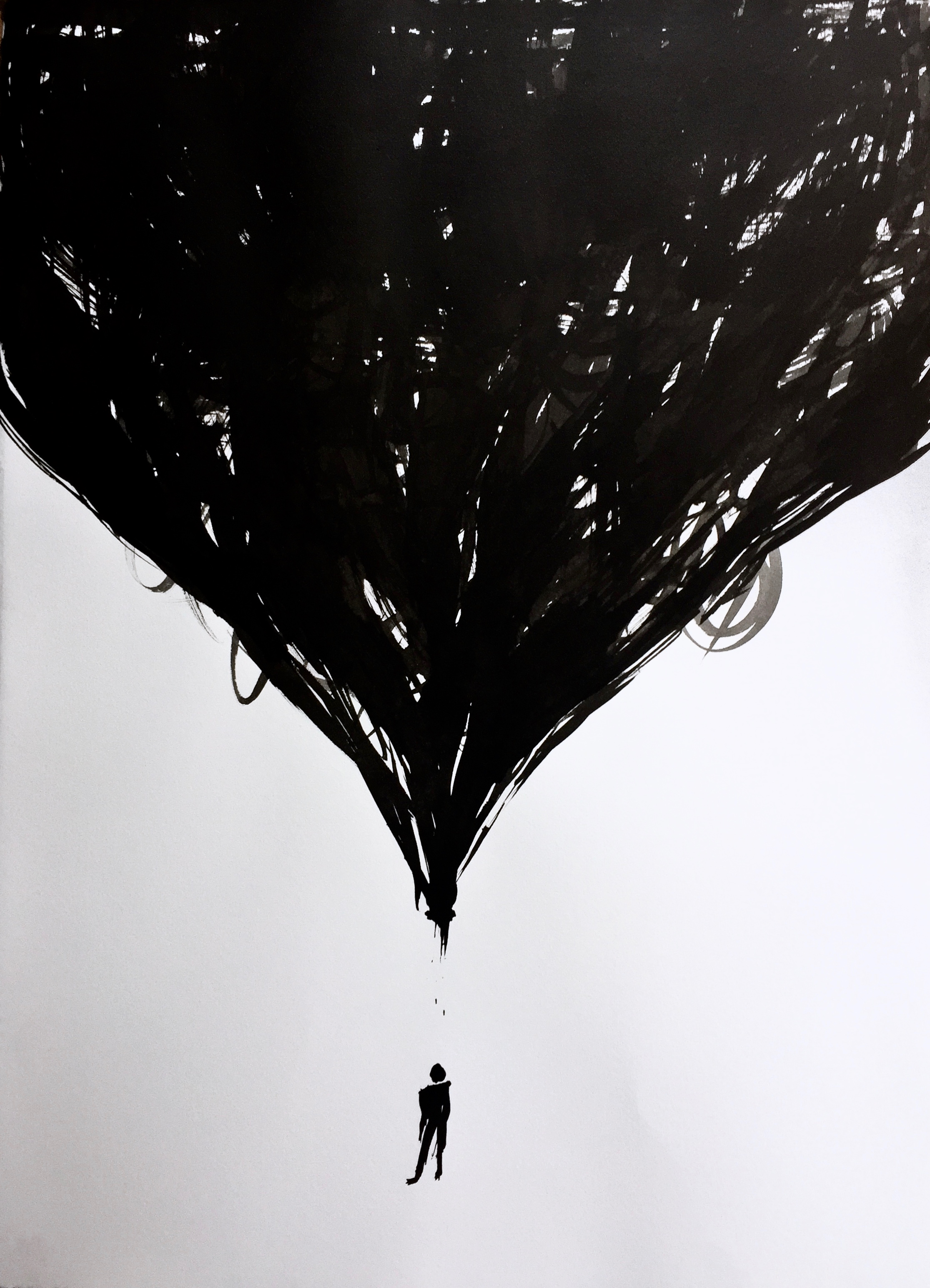

Everything That's Opposite

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What did you learn from your mother about what it means to be a girl? Are there things you wish you hadn't learned?

A. I am everything that's opposite of what she wanted me to be.

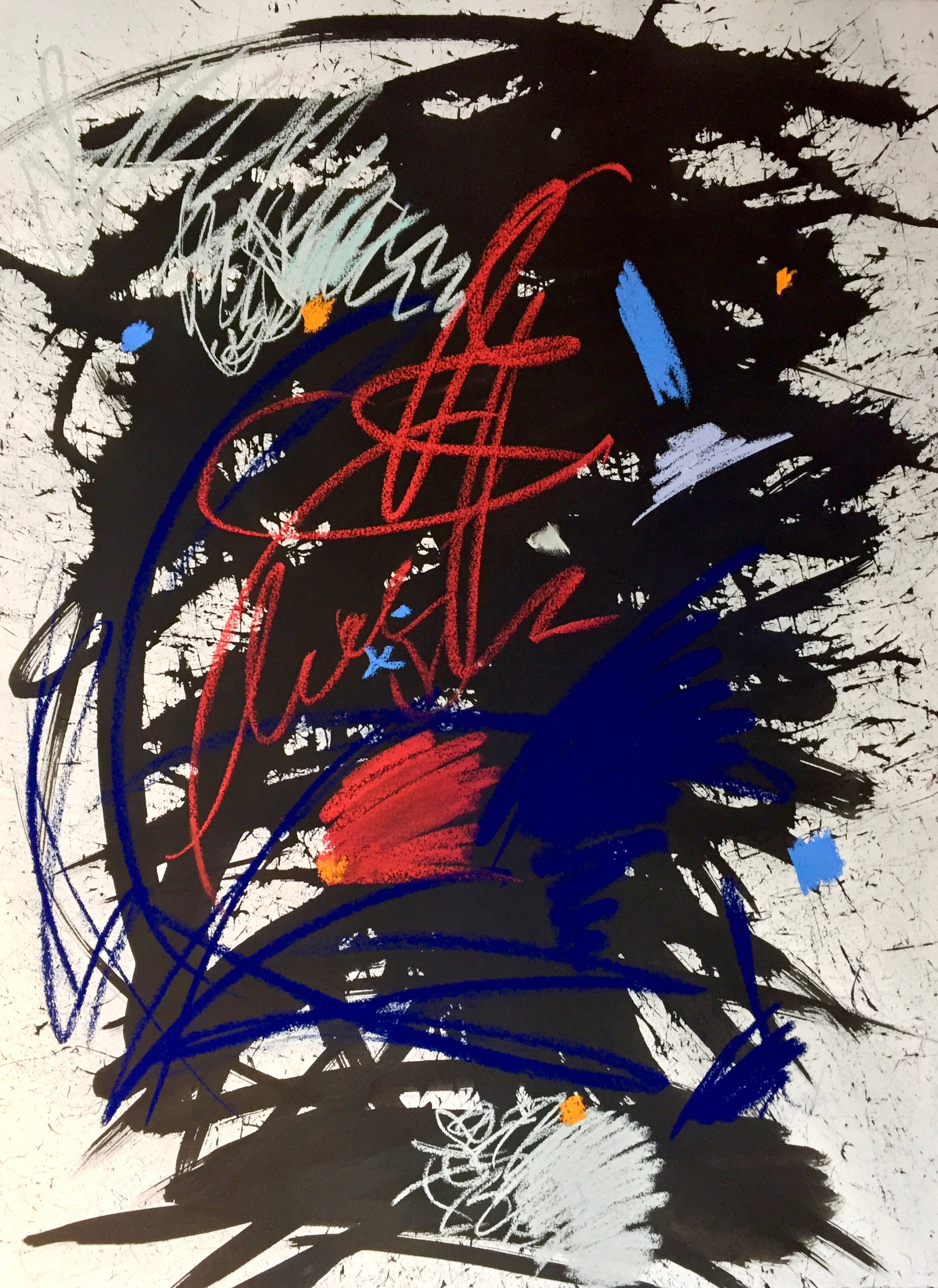

Whimsical Adult

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What is the dividing line between girlhood and womanhood?

A. Since conscious memory I've been an adult. A very whimsical adult.

Not Smart Enough For NASA

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What's one memory from when you were a little girl that stands out to you as being the most influential in teaching you what it meant to be a girl?

A. I was in math class in 7th grade. My teacher asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and I said I wanted to work for NASA. She told me I wasn’t smart enough. I don’t know if it was personal or because of my gender. She went on to be a high school guidance counselor.

A. I learned a lot of false things about what it means to be a girl. Girls don’t give anyone access to their bodies. Girls don’t speak a certain way. Girls don’t use certain words. The prevailing mosaic was this theme that girls base their actions based on what other people think. Juxtaposed with that was the equally dominant theme that girls can accomplish anything they want to do. If you decide there’s something you want to do, you can do it. I didn’t need to be afraid of trying anything or embarking on anything.

A. I have two distinct memories– Being fitted for my first bra and how uncomfortable it was. It itched and I couldn’t imagine living my whole life in this thing. When I complained my mother said, “Welcome to being a woman.” Then, in 5th grade, we had to weigh ourselves in math class in front of everyone. I was one of the tallest girls and weighed more than the other girls. Seeing everyone’s “whoa” reaction made me feel instantly insecure. I ran out of class and burst into tears. From that point on began the body issues I still struggle with today.

A. My mom flashed my sister and I with her bare breasts and told us that’s what we looked like when we wore tight shirts. It felt shameful to be a girl turning into a woman.

A. I went to Walmart one summer to pick out bathing suits. I was probably twelve years old and I recall being in the dressing room feeling immense discomfort and shame while looking at my reflection. Extreme awareness of and some degree of scrutiny about my body would continue for another 12 years or so.

A. I dated a grade 12 guy when I was in grade 9. He broke my heart ;) And after that I became very guarded and tough. Only a few years after I found God did the softness come back, but that experience, unfortunately, made me someone I pray my daughter will never become.

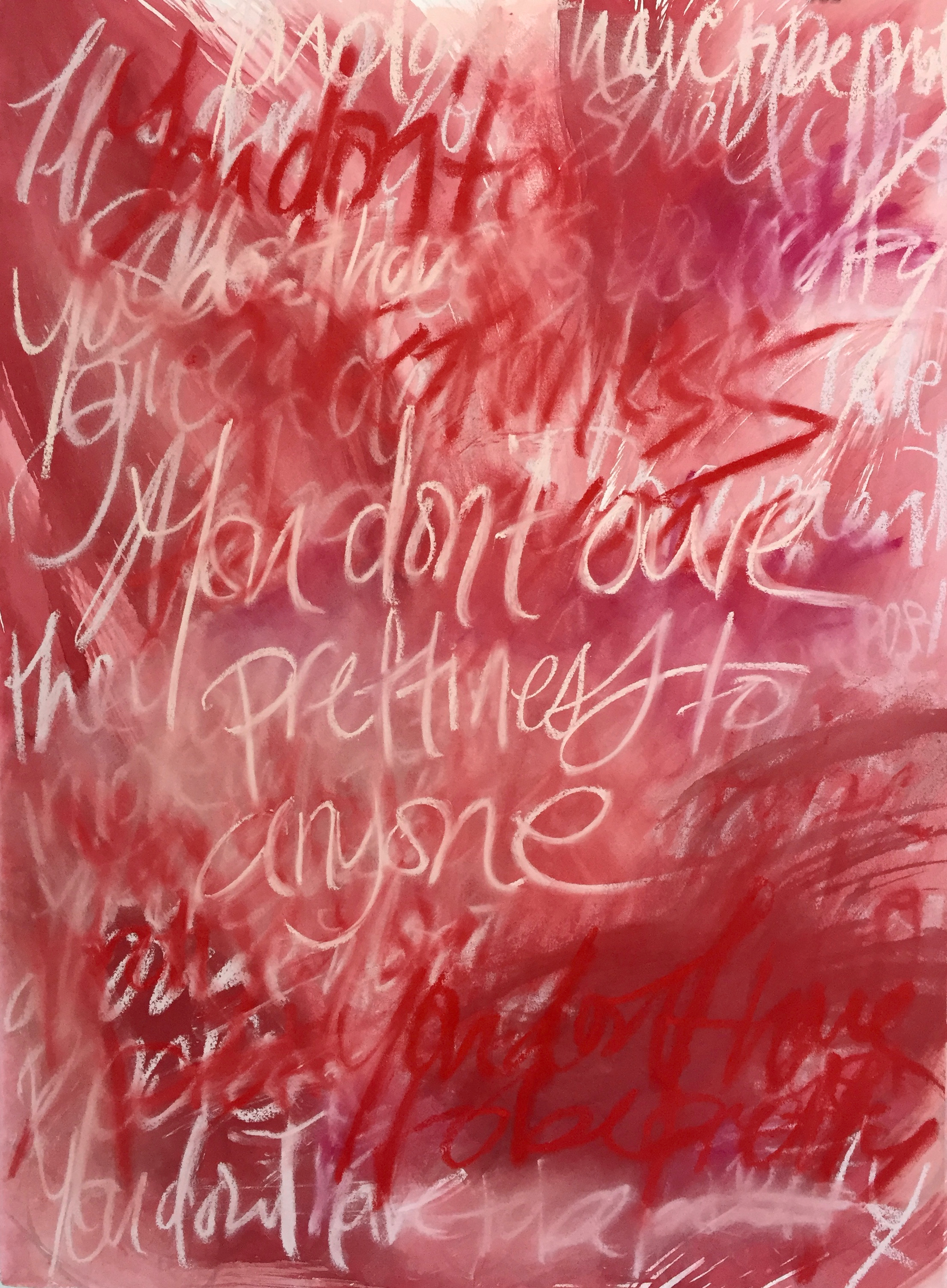

You Don't Owe Pretty To Anyone

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

" You don’t have to be pretty. You don’t owe prettiness to anyone. Not to your boyfriend/spouse/partner, not to your co-workers, especially not to random men on the street. You don’t owe it to your mother, you don’t owe it to your children, you don’t owe it to civilization in general. Prettiness is not a rent you pay for occupying a space marked “female”.' (Erin McKean)

Q. Who taught you the most about what it means to be a girl?

A. I dated a boy whose mother was this super fickle, travel-loving, satin-panties-and-silk-pajamas-wearing woman, who so many other female adults looked down on. She once cussed very loudly on stage during a magic show at school when she was startled. I adored her. She wore heels and expensive perfume, and she danced to very loud music in the living room with her sons. She was deliciously unpredictable. Something about her wildness made me step outside my box.

A. My friends in high school that wore the hijab. Veiling one’s head was the antithesis of being a girl for me for so long, because it counteracted all I heard of what it meant to be a woman in the south– i.e. show your legs while you’re young, keep your hair extra blonde, put your face on before you leave the house.

But I loved learning the intimacy, the indecision, and the empowerment so deeply rooted in each of their choices to cover their heads or not– it wasn’t blind, pushed, or bowing to pressure. They were bold in their quest to understand their bodies, and how they’d let the world and religion have them. I admired that and wanted to emulate it, and realized empowerment stretched far beyond how much skin a woman could show in an Abercrombie & Fitch ad.

A. My horse. She was a gorgeous mare who was wild and crazy but could be tamed. She just needed to be loved and cared for. We understood each other. She was my best friend.

Father/Daughter

22x30, pastel on paper, 2016

Q. Does having a daughter change the way you see your girlhood?

A. It brought to life for me the impact a present, active father changes the landscape of the way a little girl thinks. Having a girl with love and adoration for her dad makes me thankful I’m able to provide for my daughter something that I never had, but also sad that I didn’t get to experience that in my girlhood. But growing up I was never sad about the lack of strength in the father-daughter relationship. I guess I didn’t know what I was missing or how it could have impacted me differently until later in life.

In Pursuit

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. How would you describe yourself?

A. In pursuit.

Too Fat for Ballet

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What is the dividing line between girlhood and womanhood?

A. I once mentioned to my husband that I never took ballet when I was little because I was a bit chubby, and when I told a girl at school that I was getting my ballet clothes that afternoon, she replied: FAT GIRLS AREN’T ALLOWED TO DO BALLET. So, I never did, and I never told my mom why I changed my mind. My husband was so traumatized by the story, that he got me a beginner’s course at the Broadway Dance Academy when we moved to New York. I remember walking to class every Sunday afternoon, and being as excited as I probably would have been in first grade—twenty years before. It was a defining moment in my life and I realized that I should pursue being that joyful little girl, more than the pursuit of being a grown-up, mature woman. So maybe my answer will be this– there should never be a defining line. It should be a grey area where you can float between the black and white of the two seasons as needed. There’s a song that goes like this, which probably best summarizes what I mean:

But grey is not a compromise

It is the bridge between two sides

I would even argue that it is the color

That most represents God’s eyes

A. I spent most of my girlhood thinking it was intimacy with men– and then I went to college, and that happened, and in the vulnerability and aftermath, I felt like far more of a small, unprotected child than I did a mature, balanced woman. I wasn’t sad that innocence was lost or that I would be ruined for the future. Now, to me, it’s confidence. It’s been about realizing that getting engagement isn’t the greatest achievement of your life or a grand leap forward for humanity, that it’s lame to ditch your friends for a guy, to stop running from female friendships and instead foster them with everything you have.

Chainsaws and Sawdust

22x30, pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What made you feel safe as a girl?

A. The smell of my dad's clothes-- chainsaw oil and sawdust.

Things Fall Apart

Q. If you could tell your girlhood self something, what would it be?

A. Sometimes being pleasing isn't the answer. Sometimes things just need to fall apart.

Campfire and Wine

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. When you think back on your girlhood, what memory do you associate with your mom?

A. I picture her with a glass of wine next to a campfire.

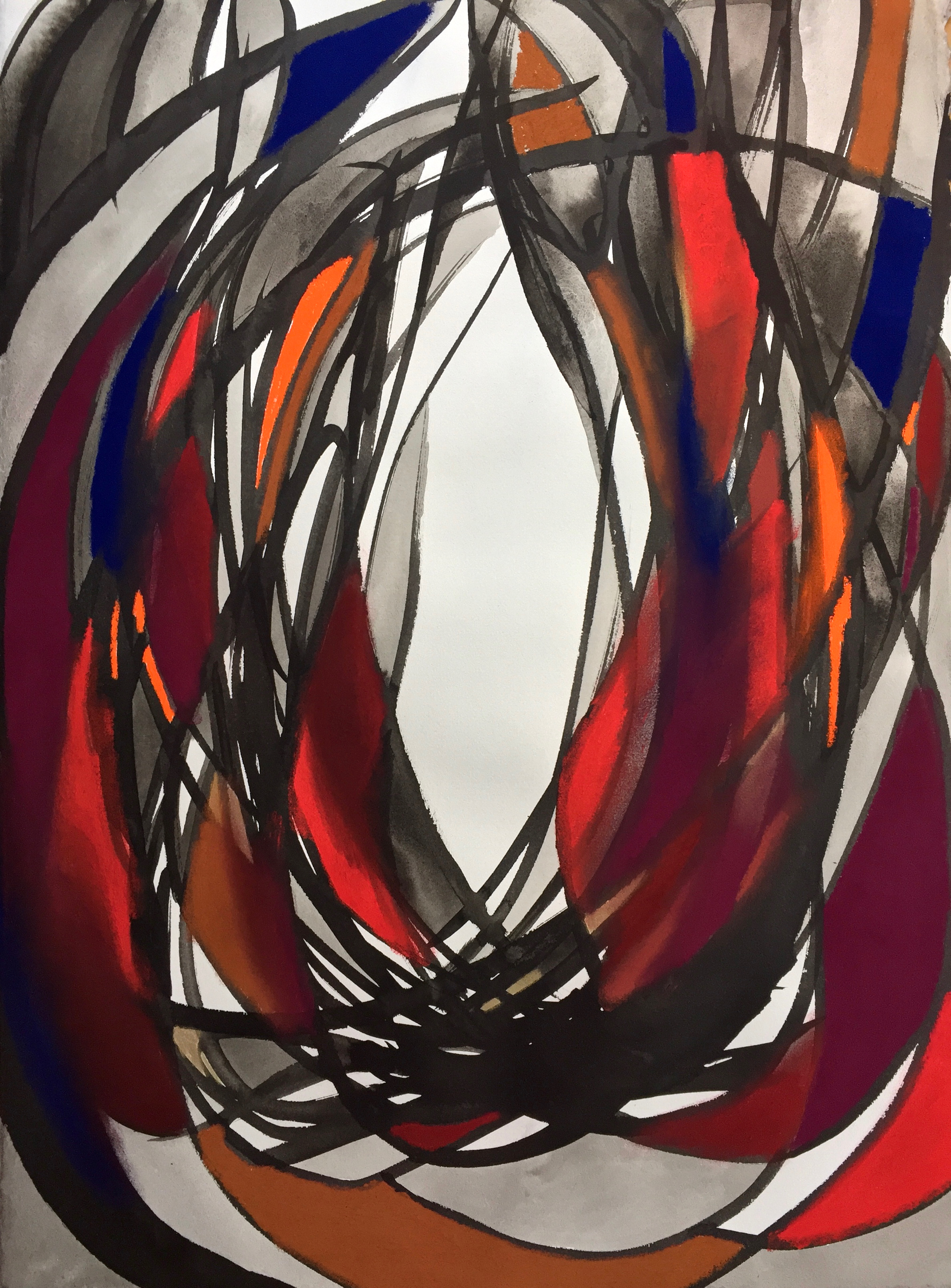

Creation

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What does being a girl mean to you?

A. "Having half the potential of creation in me."

Mad Money

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What did you learn from your mother about what it means to be a girl?

A. She bought a house, boat, and a BMW before she married my dad so she’d never feel entirely reliant on him, and told me I should do the same. She told me never to be without “mad money”– cash you should keep your whole life in case you have to leave town or a man very quickly.

Girl

22x30, ink on paper, 2016

Q. What does being a girl mean to you?

A. Some blend of revolt, of redefining the language of each day, and realizing that compromise doesn’t mean concession.

A. The fact that my name means ‘girl’ always annoyed me growing up. It seemed ironic, superficial– unlike me. Now that I’m older, it no longer feels that way. I don't see the definition as a gender. I see it as an act of resistance. A quiet flag rising amidst the conflict.

What is her name?

Girl.

It means living in the tension between strength and vulnerability and knowing when it’s time for each.

We Are Not the Same

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. Do you consider yourself a feminist?

A. It’s not necessarily that simple anymore. But, yes, I do. The path got lost between the sixties and now. Equal rights became this pursuit of sameness. Equality is obtuse. We thought that in order to have equality we had to fight to be the same. We lost the definition of what makes us different. We thought that to be in a position of power we had to act the same way as men, and we lost our way. We became dictated to by society and the marketplace and were vilified for that. In college, I distanced myself from the label because I felt like it disqualified me from being desirable. Femininity, grace, empathy, maternal instinct are all powerful virtues. Amazingly complementary to what men offer.

A. Yes, but it took me until after grad school to understand it and say it. I was in the Middle East, and a fifteen year old girl in one of our programs had run off with her eighteen year old boyfriend, and while that’s not common for this to happen, her dad wanted to kill both of them– or likely just said it out of hurt and the hellish oppression in which the whole family lived. The uncle showed up at our office with a gun, and I had to shut the door on him. When the whole debacle was resolved late that night, I realized I had no business being so loud and outspoken about the rights of women in one country and acting so shy about them in my own. There was no way in hell I was watching a gun come that close to me in the name of what I believed, and staying quiet so as not to offend someone who’s only watched Fox News or posted on Facebook about it.

A. I used to. But as I got older, and especially over the past five years when I worked in a very traditional male dominant set up, I got tired of wanting to prove myself and women in general. I had a revelation that I don’t have to be a man in a man’s world, but that I need to figure out how to be a woman in a man’s world. I’ve grown softer, and ever since I’ve actually seen more change in the areas that I used to fight for because of that.

A. Yes, I wholeheartedly believe in equal rights and standing between women and men. My upbringing was as one of two girls– you could do anything. There was no glass ceiling. I would never have called it feminism, but I see it as that now. It wasn’t your gender that defined what you could or could not do.

A. Now that I’m older I do. I didn’t realize when I was young that I needed to be one. Equality is something both men and women haven’t fully grasped.

A. Yes, I believe we are the more powerful sex.

A. The term feminist in our current culture? No. I think being a feminist should be more about becoming a woman, than a man.

A. I do. I didn’t used to. The political opinions in my family were very male and very strong. I was raised thinking feminism was aggressive, ugly, and angry. Now, every woman I know is a feminist, even if she won't admit it. It’s not about being the same as a man but receiving the same chances. Some women aren’t given those chances at all.

A. Yes, it never occurred to me not to be.

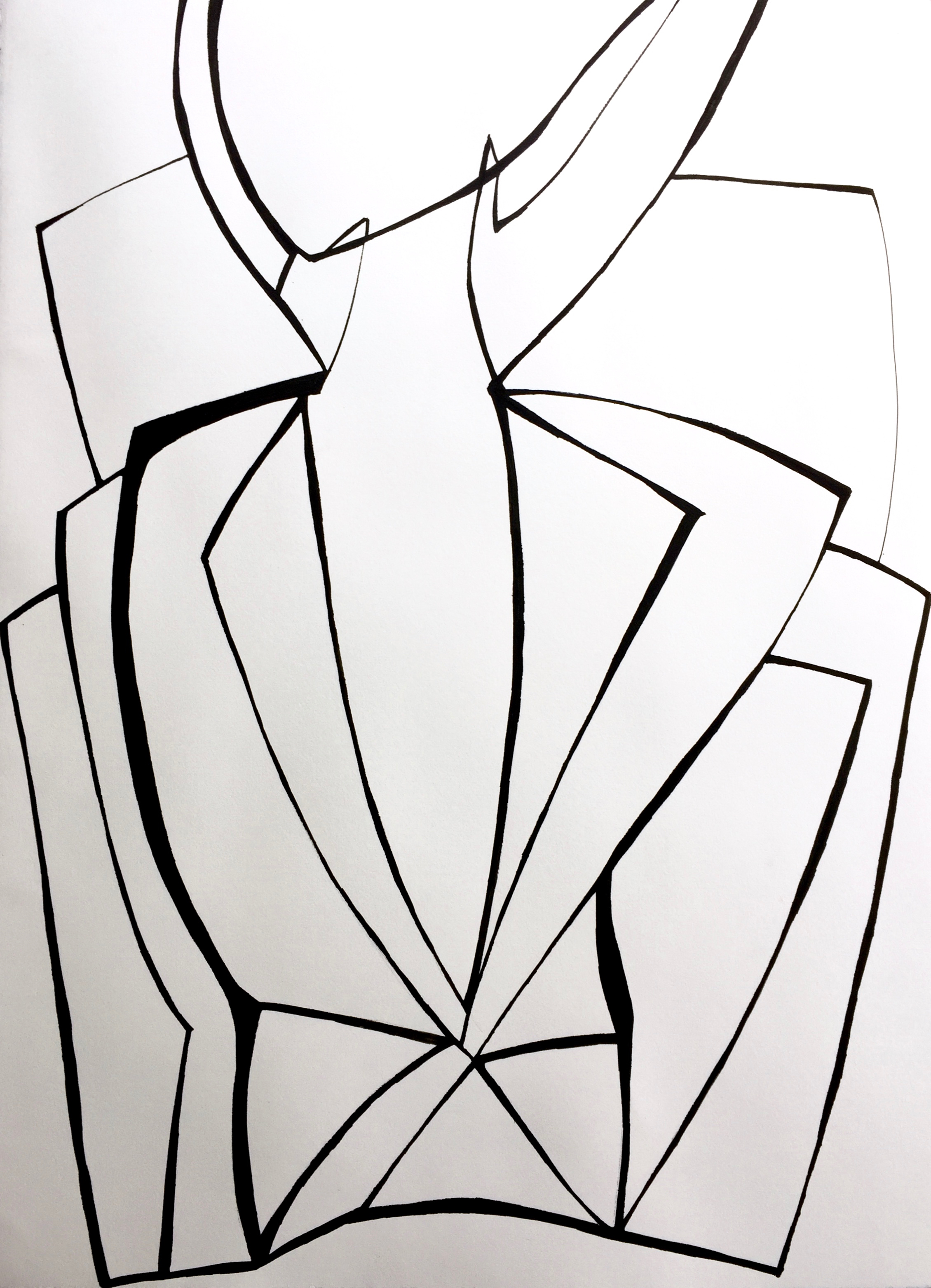

A Box of Boxy Suits

22x30, ink on paper, 2016

Q. What’s one memory from when you were a little girl that stands out to you as being the most influential in teaching you what it meant to be a girl?

A. While playing dress-up in my mom’s closet at a very young age, I tried on a suit that I found stuck in the very back of her clothes rack. The pocket was filled with her old business cards from when she still went by her maiden name and not my father’s. When she came upstairs and found me with the cards, she told me for the first time about the career she’d had before she had me. She told me she wore suits– these boxy, androgynous, custom-made pantsuits– because nobody took women seriously in technology at the time. She told me she once had a career like my dad’s– in the early days of technology– and that she was one of the top-ranking saleswomen for her company in the nation. She also told me she went by her maiden name until I went to kindergarten because her career had been made in that name. And she also told me she was the first in her family to go to college, that she paid for it by herself working at a grocery store, and that while she never wanted to stop working, she felt an urge in the weeks after she had a daughter not to return to the office because she wanted me to stand on her shoulders. I remember feeling somehow both very proud, that she had been so good, and very sad, because I saw how proud she was of her past. It would make me sad many times again over the years, when technology kept advancing as did my dad’s career in the field, and my mom didn’t have access to keep up with the sector and struggled to use an iPhone or laptop. I think it was my first lesson in sacrifice, although I didn’t know the word then. It’s the sacrifice so intimately and uniquely associated with being female. I realized being a girl came with more decisions than being a boy, and that I would have to make those decisions one day on my own, too.

Don't Feel Like a Girl

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What does being a girl mean to you?

A. I guess I don't feel like a girl anymore.

Fred Astaire in the Rain

22x30, ink on paper, 2016

Q. When you think back on your girlhood, what memory do you associate with your mom?

A. She looms so large in everything. I always wanted to wake up early, but she would scream at me for waking her up. I would make my bed and lay on top of the covers. I would open drawers softly, so they made no noise, but one time she pulled me out of bed by the hair, hitting me, and I put my arms up and she said, “I can’t believe you’d hit your mother.” She did a cute thing once, though, when I worked at an ice cream stand. She would come visit me, and when it rained, she would do Fred Astaire dances for the employees in the rain.

Normal Girl

22x30, ink and pastel on paper, 2016

Q. What’s one memory from when you were a little girl that stands out to you as being the most influential in teaching you what it meant to be a girl?

A. I got into a screaming fight with my mom at my grandma’s house because I wouldn’t wear a dress to dinner. She just kept yelling,

“Why can’t you be a normal girl?”

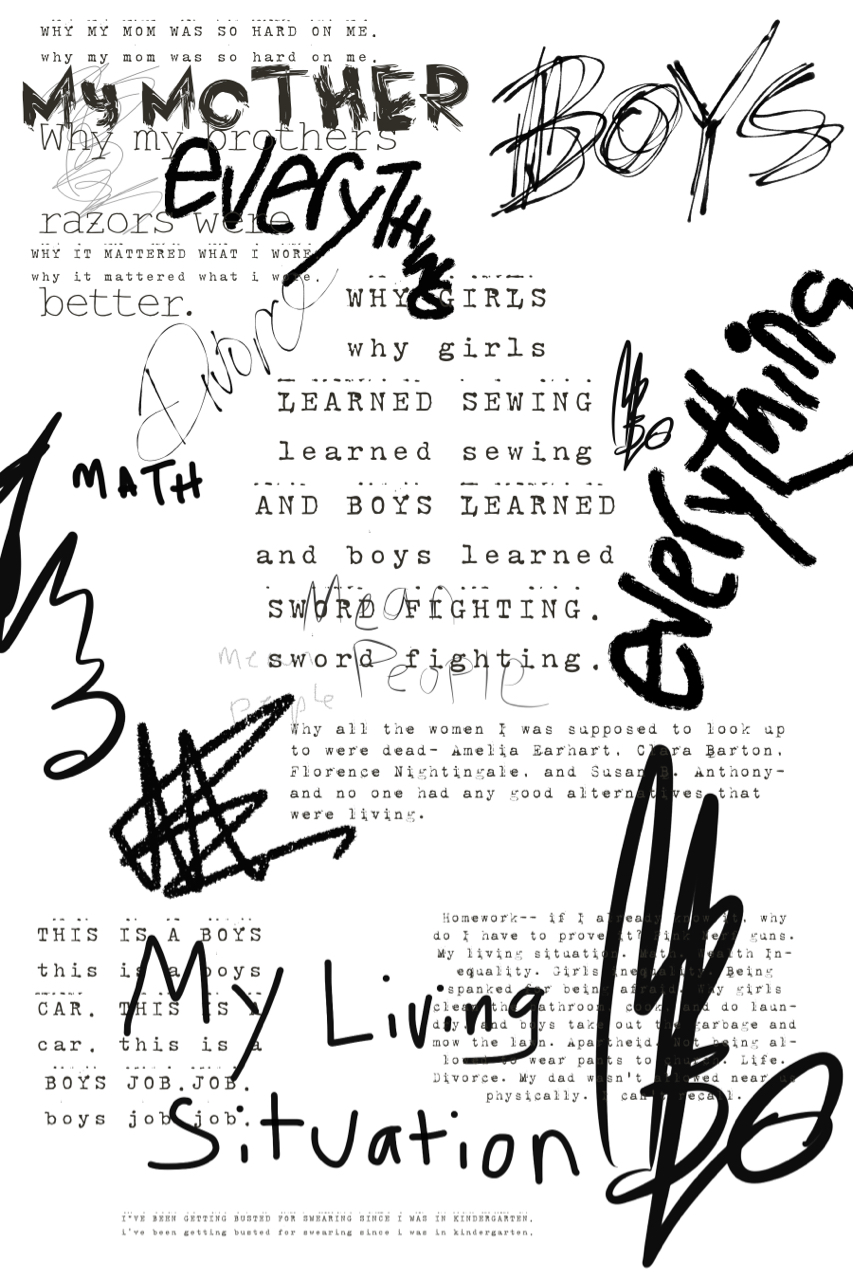

Girls Learn Sewing, Boys Learn Swordfighting

22x34, inkjet on mylar, 2016

Q. What didn't make sense growing up?

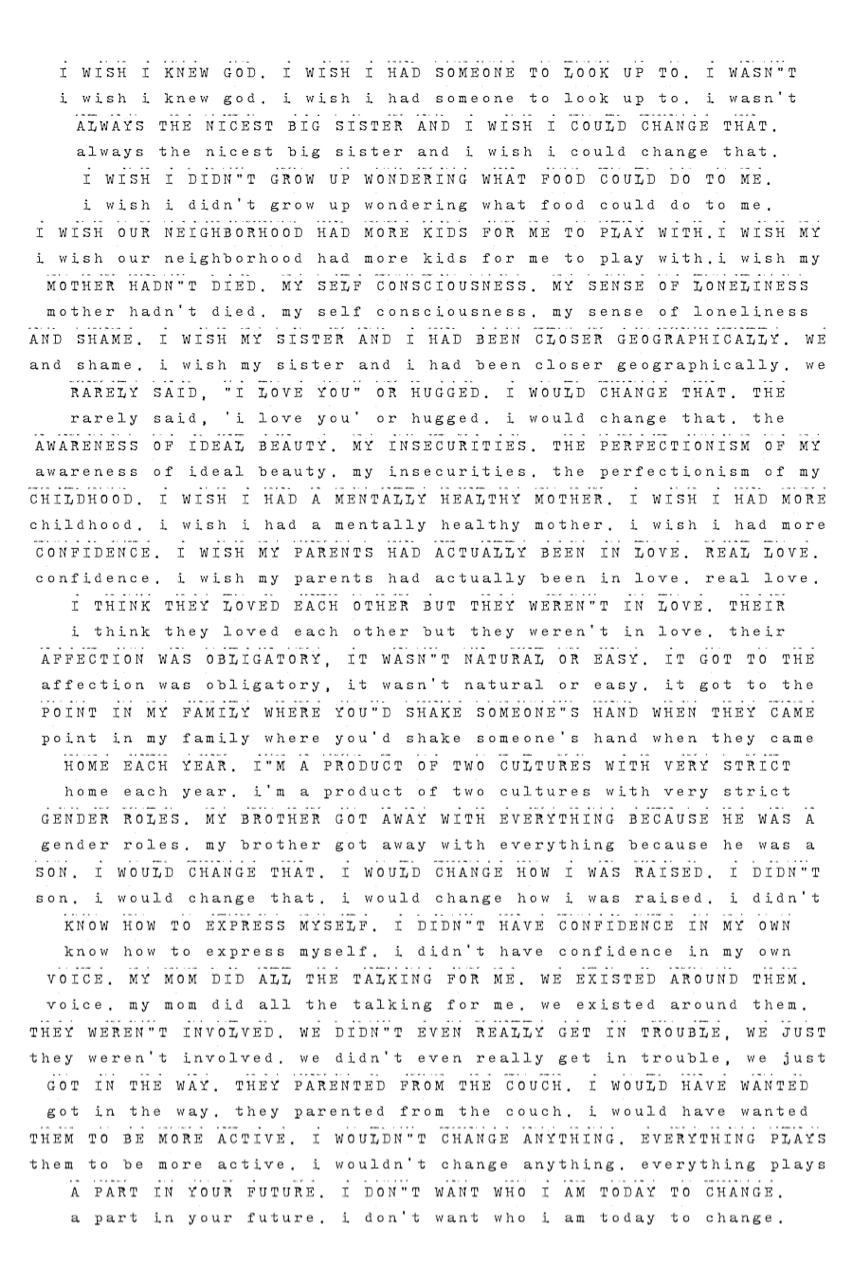

I Wish

22x34, inkjet on mylar, 2016

Q. If you could change one thing about your girlhood, what would it be?